Curse of living with disability

HARARE - Shunned because of the physical deformities they were either born with or acquired later in life, people with disabilities are often forgotten and ridiculed.

Loreen Chikoto was born with dwarfism, a genetic defect that makes her smaller than the average person.

When she started dating, people found it odd and when she got pregnant the comments and taunts were even worse.

“Often, I would hear people saying ‘ndiani akashinga kurara nekamunhu aka, haanzwewo tsitsi here? (who was courageous enough to sleep with such a person, do they not have any mercy for her?). Unbeknown to them is that I am married and was simply doing what most married people do,” she said.

According to Section 22 of the Constitution, the State, all institutions and government agencies must recognise the rights of persons with disabilities and must afford them the respect and dignity they deserve.

Section 83 also mandates the State to ensure that people with disabilities realise their full mental and physical potential through provision of State funded education, access to medical treatment and protection from abuse.

In September 2013, Zimbabwe ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

Among some of the provisions of the Convention is the right to access justice, freedom from exploitation violence and abuse and protecting the integrity of the person.

Recently, government through the ministries of Social Welfare, Justice, and Women Affairs held consultations to align the Disabled Persons Act to the Constitution.

The exercise was aimed at mainstreaming disability issues as an integral part of the relevant strategies of sustainable development.

During the outreach programmes, some of the persons with disabilities complained that they are judged when seeking medical treatment for sexually transmitted diseases(STIs).

They said they are frowned upon and asked how they contracted the STIs when they visit clinics or hospitals.

Others explained how children with disabilities are deprived of education and often end up dropping out of school.

“Some parents with physically challenged children hide them from society, deprive them of education and infringe on their rights to associate with others,” said one woman.

Senator Anna Shiri told the Daily News on Sunday that there was a serious need for extensive advocacy on the rights and needs of people with disabilities.

She said very few people know how to handle or approach people with disabilities, prompting society to shun or ignore them in key decision areas.

Shiri said issues to do with people with disabilities are no longer a welfare issue but a human rights concern as such people do not require handouts anymore but need to be economically empowered to take care of themselves.

The senator said employment issues are very important as people with disabilities are not seriously considered for employment regardless of their qualifications.

“There is very little awareness on issues concerning people with disabilities. People think they will be a burden when they employ them despite being able to perform the tasks. In Senate, there are only two people representing people living with disabilities while in the Lower House there is none.

“People with disabilities find it very hard to get jobs because of the attitude society has,” she said.

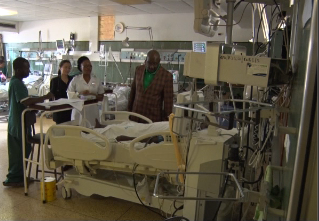

Shiri added that people with disabilities often face the challenge of being wrongly diagnosed because of poor communication between the patient and doctor or nurse.

She said there are no information pamphlets in braille which can be used by the visually impaired or sign language interpretation often leaving these people in the dark on health related matters.

“Many public facilities are not friendly to people living with disabilities. Hospitals, schools and even churches are not accessible to people with disabilities.

“Toilets meant for these people are not one size fits all. Just because it can fit a wheelchair does not mean it was done properly.

“Different disabilities require different adjustments hence the need for specialist architects to build proper structures that can accommodate all.”

“There is need to mainstream disabilities because the Sustainable Development Goals clearly state that no one should be left behind.

“All developmental concerns should include people with disabilities. In 2015, only one disabled person in the whole country benefitted from the revolving loan fund and that is deplorable,” she said.

Shiri said people with disabilities are being abused everyday but their cases are not reported because society does not respect them as human beings.

She said people with disabilities should be self-represented and not have others assume what challenges they face.

The senator, representing people living with disabilities, said only if the UNCRPD is domesticated will the rights of persons with disabilities be upheld and respected.

“The entire legal process is traumatising to a person with a disability. For example, reporting a case can be a task for someone using sign language because a police officer does not understand sign language and when it finally goes to court, interpreters are not readily available,” Shiri said.

She said the National Disability Board members were not part of the government consultation process making it flawed.

Executive director for Community Working Group Itai Rusike said it is unfortunate that people living with disabilities still continue to experience shame, stigma and discrimination.

Rusike said as people living with disabilities constitute 10 percent of the population, the resource allocation to the sector does not reflect their growing need to be fully supported.

He added that people with disabilities are also sexual beings like able bodied people and must have access to information and resources to make informed choices on their sexual and reproductive health.

“The Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights (SRHR) of persons with disabilities are often overlooked by the communities and service providers yet they have the same needs for SRHR services as everyone else.”

“People with disabilities actually have greater needs for SRHR education and care due to their vulnerability to abuse, yet the country has not done enough to popularise and translate policy documents including IEC materials into the relevant materials understood by people living with various forms of disabilities,” he said.

Rusike also said the training curriculum for health personnel needs to have a human rights approach for people living with disabilities and must also include basic training in sign language, braille and provision of disability-friendly facilities in all our health centres.